Relational databases are one of many kinds of databases. They have been useful in the humanities because we often deal with complex evidence that does not fit easily into single spreadsheets. Because humanities scholars frequently ask questions about the relationships between things, relational databases provide a structured environment in which to document, query, and visualize these connections.

Fundamental Considerations

What question(s) will a database allow you to answer? Once you have a research question, you can specify it to suit the sources you find that have relevant information.

For example:

What is the importance of foreign authorship in the development of French prose fiction? –> (How many novels printed in Paris during the 18th c. were written by authors who were not French?)

How does the application of different book censorship/privilege policies affect access to prose fiction in the 18th c.? –> (Which titles are unique or recur in different manuscript sources documenting book seizures, privileges, etc.)

Were eighteenth-century engineers in Brittany a cohesive social group? –> (What picture of engineers emerges from tax roles?)

How did participating in highway construction impact reactions to political events in the spring of 1789? –> (Is there a connection between the spatial distribution of highway construction work and highly polarized rhetoric captured in village complaints at the beginning of the French Revolution?)

How will you use the database to answer these questions?

What kinds of queries/visualizations/maps will it allow you to perform/create?

How do you create a relational database?

A relational database, as its name suggests, helps you relate/match information that occurs in separate tables. It does this by connecting keys (a unique identifier for a single piece of information).

Develop the structure (schema) based on your goals and source material. “Normalizing” your data means breaking it down into multiple tables even when it may not present this way in real life.

“Source-oriented”

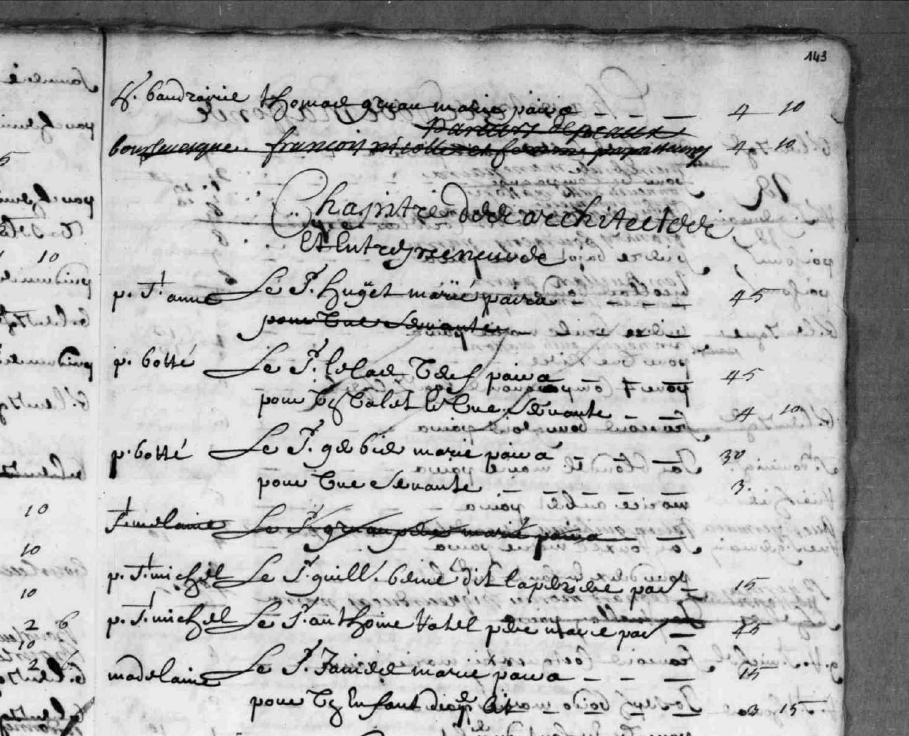

If you are creating a database to replicate as much as possible an individual or set of similar sources, you may want to closely relate the design (the schema) to the original source structure.

“Method-oriented”

If you are working at a composite level, you can design your database to capture specific kinds of information that will help you answer your research question. In this case it is important to document the provenance of the information in each cell.

Normalizing Principles

Entities

These are the objects of analysis (but are not necessarily “things”).

Entities could be coffee cups, bikes, colleagues, transactions, or library call numbers.

An entity’s attributes become the columns in your table. An attribute that is unique to an entity should be its primary key.

Keys

A primary key is a special column in a table whose values (perhaps numbers, perhaps names) are unique within that column. A primary key has three qualities: 1) it is unique across all records in the table; 2) it has a non-NULL value for each record in the table for the entire lifetime of the record; 3) its value never changes during the lifetime of the record.

Primary keys are often set up as auto-increment integers or as randomly generated unique IDs.

A foreign key is a value in a table that is a primary key from a different table. Foreign keys need not be unique. Foreign keys make relational databases possible.

Relationships

| relationship | description | example |

|---|---|---|

| one-to-one | one X has only one Y | a building has one address |

| one-to-many | one X has many Ys | an author writes many books |

| many-to-many | many Xs have many Ys | many historians attend many conferences |

Putting this into action

Harvey Quamen, guru of humanities databases, suggests the following process for determining what to do with your material:

- Identify the nouns in your data. These are probably going to be your entities. Each entity will get its own table.

- eliminate lists of information in one fields

- do not duplicate information

- each table should describe only one entity

- do not store anything you can calculate (age vs. birthday)

- design tables so that adding new information creates new rows, not new columns

- design tables to contain as few NULL (blank) values

- each column should contain only one type of information (e.g. do not mix different data that could be broken down into separate columns)

-

Build out the relationships in your data. Move repetitive information into new tables.

-

Make sure that a table’s columns are dependent on that table’s primary key. Each column should be an attribute of the entity. E.g. it functions as an adjective.

Exercise 1

Navigate to this Google Sheet of “bad data”.

- Thoughts about the layout?

- Thoughts about data entry?

- How would you describe the relationships between the information in each column?

- Would this be a good candidate for a relational table?

Using a piece of scratch paper, sketch out a new schema for the information in this single table.

- What tables would you create? What would be the columns in those tables? How are the tables related to each other (e.g. which primary keys act as foreign keys in other tables?)

Compare your schema with this one.

-

What does this schema allow for?

-

How does it incorporate data external to the original source?

Notes on documentation

- Document where information originates

- Document any data transformations (e.g. standardization of dates, etc.)

- Github repository wikis are an excellent place to preserve documentation.

Dealing with uncertainty

As the taxpayer data demonstrates, sources will often have gaps that we cannot fill. There will be NULL values in your tables. Too many NULL values may suggest that a database is not the best solution for capturing your data.

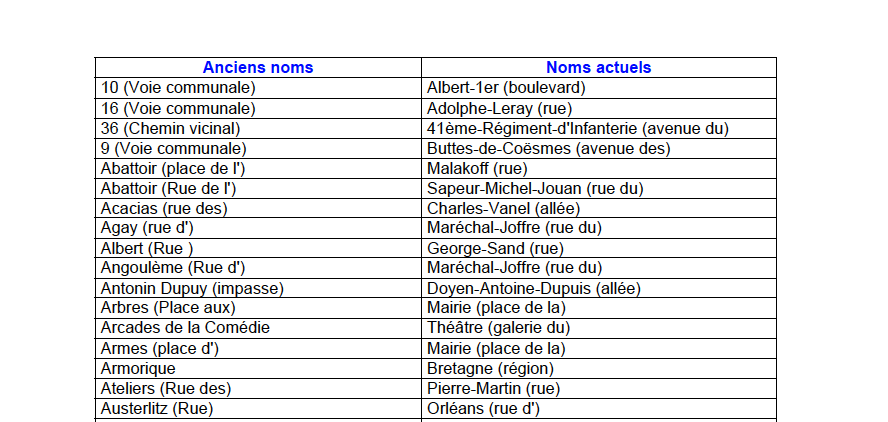

Sometimes, data is available but it is difficult to read or disambiguate. Which city does this document describe? Which foreign minister? Developing strategies for accounting for “fuzzy” data will help you here. The key is to be consistent in the manner of indicating fuzziness.

Data standardization/Linked data

While you may want to preserve original spellings (including abbreviations, mistakes, or variants) in one set of table fields, in another set you may wish to normalize these and connect them to external resources.

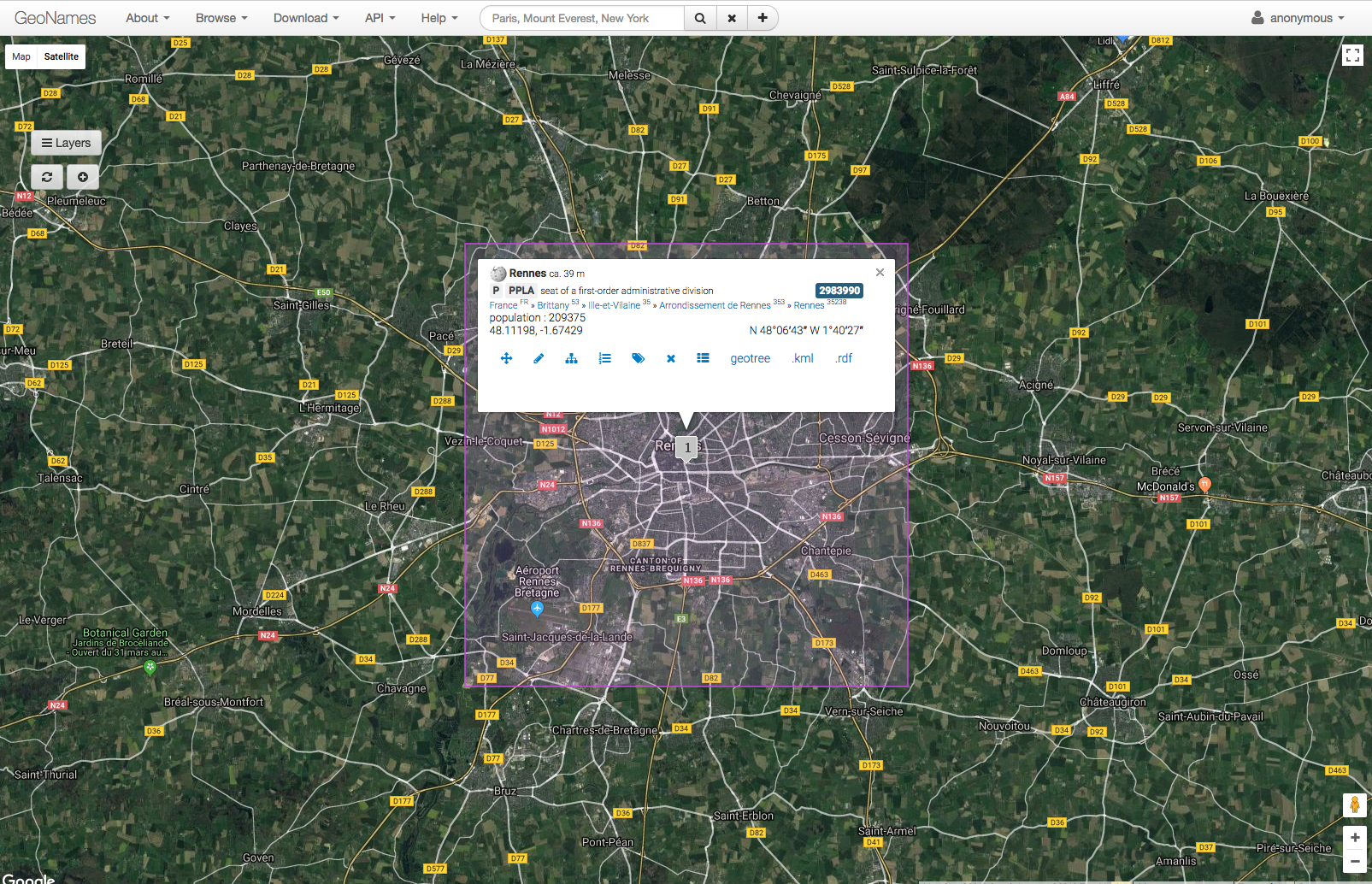

For example, in the taxpayer table we saw that the Street table included information that was not found in the original tax records. The location of the city where this street is found is not a transcription of latitude and longitude coordinates like it is fr the Street CoordinateLocation. Instead, it includes a link to the Geonames record for the city of Rennes (http://www.geonames.org/2983990/rennes.html)

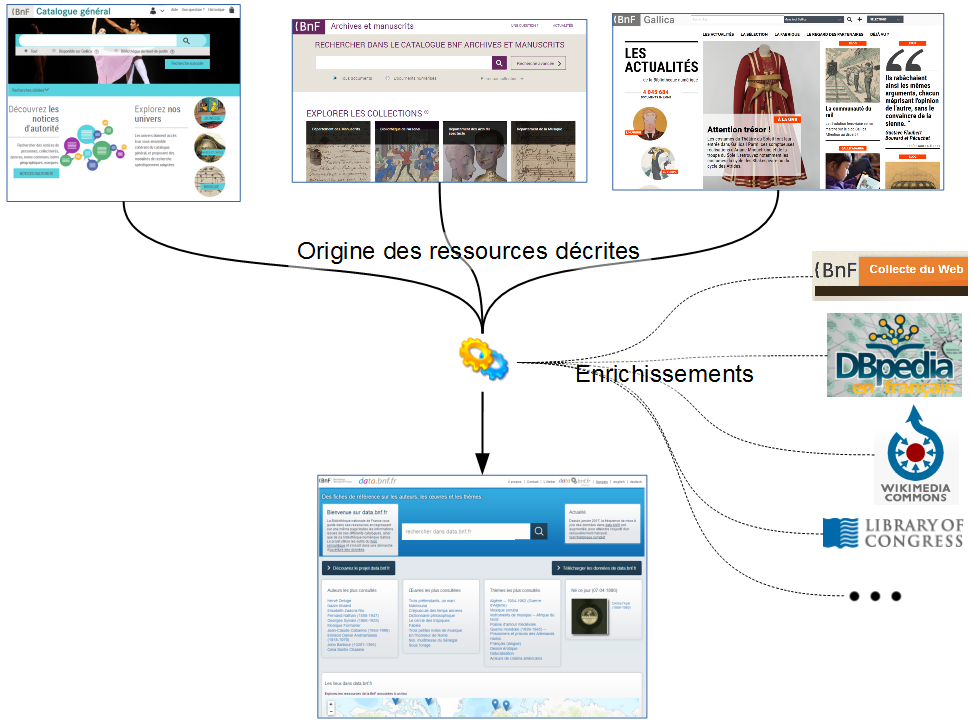

Implementing linked data in your database has significant advantages.

- It can save you time in determining what the coordinates (or other attributes) are for an entity. You can identify authority records for people, places, subject keywords, historical periods, etc. that have often been carefully curated by the the library/archive or other scholarly communities.

- Because heritage institutions and scholarly projects are making their data available to individual researchers, we now have an opportunity to see where our datasets overlap. If we all use a different set of coordinates for the city of Rennes or we use different forms of book titles, we lose the chance to see new kinds of relationships in humanities research.